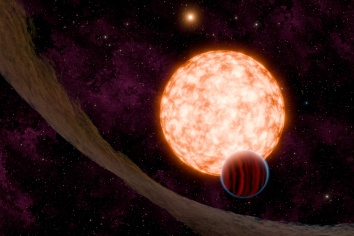

An artistic interpretation of the TIDYE-1 system. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/R. Hurt, K. Miller (Caltech/IPAC).

20 November 2024

Today, astronomers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and The University of Texas at Austin announced the discovery of the youngest planet ever found using the transit method. With this method, a planet is detected when it passes between its host star and the observer. The planet, named TIDYE-1b, is roughly the size of Jupiter and is an estimated 3 million years old. To put that age into perspective: If Earth were a 50-year-old person, TIDYE-1b would be a 2-week-old infant.

Results of the discovery were published in the journal Nature.

“When we’re looking for transits, we’re looking at the star’s brightness over a period of time,” said Madyson Barber, lead author of the study and a graduate student at UNC-Chapel Hill. “When the planet comes in front of the star, we see a little dip in that brightness, because it’s blocking some of the star. So, we’re looking for those repeated dips in the light curve.”

Astronomers have found dozens of transiting planets in the 10- to 100-million-year-old range, but younger planets have proven more elusive. A key reason why young planets are difficult to find is due to the thick, view-blocking protoplanetary disks of debris that form around stars in the first 5 to 10 million years of life.

However, the star that TIDYE-1b orbits has a misaligned disk, leaving the planet visible. The origin of that misalignment is still a mystery, and one that baffles astronomers.

“Planets form in disks, and what you’d expect is the star, the planet, and the disk to all be aligned,” said Andrew Mann, associate professor of physics and astronomy at UNC-Chapel Hill and co-author of the study. “The really weird thing about this system is the planet has an orientation that agrees with the star, but the disk is way off. It’s something like 60-plus degrees off.”

The research team used survey data and observations from several telescopes to detect and confirm the presence of TIDYE-1b. This included NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) and the Hobby-Eberly Telescope at UT Austin’s McDonald Observatory. Through their research, the team has found that TIDYE-1b’s atmosphere is likely still inflated due to heat left over from its formation. They also determined that the planet only takes a week to orbit its star.

“This system offers an unprecedented view of what planets look like right as they're done forming - if it's even done yet!” said Adam Kraus, professor of astronomy at UT Austin and co-author on the study.

Follow-up observations from TESS, the W.M. Keck Observatory, and McDonald Observatory are expected to establish the planet’s mass and composition, how its atmosphere compares to the surrounding disk material, and whether the planet is still growing.

With TIDYE-1b – and future discoveries like it - astronomers have a unique opportunity to study the early formation of planetary systems. That, in turn, provides important insight into how our Earth and solar system came to be. “This proves that we can find these young systems,” Barber said. “So now we know we should be looking for more, and if we can make a population of these young systems, then we can draw even more conclusions.”

“This is just the tip of the iceberg,” added Kraus. “New observatories and new instruments will reveal many more planetary systems like this and will give us an exquisite view of how these planets are being built, as they're being built.”

UT Austin scientists on the research team include Adam Kraus, Gregory Mace, Matthew De Furio, Daniel Jaffe, Erica Sawczynec, and Benjamin Tofflemire. This piece is based on a press release from UNC-Chapel Hill.

An artistic interpretation of the TIDYE-1 system. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/R. Hurt, K. Miller (Caltech/IPAC).