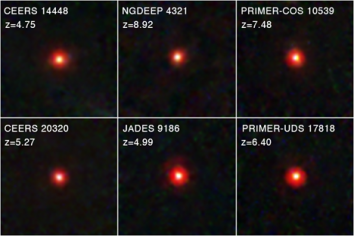

In December 2022, less than six months after commencing science operations, NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope revealed something never seen before: numerous red objects that appear small on the sky, which scientists soon called “little red dots” (LRDs). Though these dots are quite abundant, researchers are perplexed by their nature, the reason for their unique colors, and what they convey about the early universe.

A team of astronomers, including several from UT Austin, recently compiled one of the largest samples of LRDs to date, nearly all of which existed during the first 1.5 billion years after the Big Bang. They found that a large fraction of the LRDs in their sample showed signs of containing growing supermassive black holes.

“We’re confounded by this new population of objects that Webb has found. We don’t see analogs of them at lower redshifts, which is why we haven’t seen them prior to Webb,” said Dale Kocevski of Colby College in Waterville, Maine, and lead author of the study. “There's a substantial amount of work being done to try to determine the nature of these little red dots and whether their light is dominated by accreting black holes.”

A Potential Peek Into Early Black Hole Growth

A significant contributing factor to the team’s large sample size of LRDs was their use of publicly available Webb data. To start, the team searched for these red sources in the Cosmic Evolution Early Release Science (CEERS) survey before widening their scope to other extragalactic legacy fields, including the JWST Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey (JADES) and the Next Generation Deep Extragalactic Exploratory Public (NGDEEP) survey.

The methodology used to identify these objects also differed from previous studies, resulting in the census spanning a wide redshift range. The distribution they discovered is intriguing: LRDs emerge in large numbers around 600 million years after the Big Bang and undergo a rapid decline in quantity around 1.5 billion years after the Big Bang.

The team looked toward the Red Unknowns: Bright Infrared Extragalactic Survey (RUBIES) for spectroscopic data on some of the LRDs in their sample. They found that about 70 percent of the targets showed evidence for gas rapidly orbiting 2 million miles per hour (1,000 kilometers per second) – a sign of an accretion disk around a supermassive black hole. This suggests that many LRDs are accreting black holes, also known as active galactic nuclei (AGN).

“The most exciting thing for me is the redshift distributions. These really red, high-redshift sources basically stop existing at a certain point after the Big Bang,” said Steven Finkelstein, a co-author of the study at the University of Texas at Austin. “If they are growing black holes, and we think at least 70 percent of them are, this hints at an era of obscured black hole growth in the early universe.”

Contrary to Headlines, Cosmology Isn’t Broken

When LRDs were first discovered, some suggested that cosmology was “broken.” If all of the light coming from these objects was from stars, it implied that some galaxies had grown so big, so fast, that theories could not account for them.

The team’s research supports the argument that much of the light coming from these objects is from accreting black holes and not from stars. Fewer stars means smaller, more lightweight galaxies that can be understood by existing theories.

“This is how you solve the universe-breaking problem,” said Anthony Taylor, a co-author of the study at the University of Texas at Austin.

Curiouser and Curiouser

There is still a lot up for debate as LRDs seem to evoke even more questions. For example, it is still an open question as to why LRDs do not appear at lower redshifts. One possible answer is inside-out growth: As star formation within a galaxy expands outward from the nucleus, less gas is being deposited by supernovas near the accreting black hole, and it becomes less obscured. In this case, the black hole sheds its gas cocoon, becomes bluer and less red, and loses its LRD status.

Additionally, LRDs are not bright in X-ray light, which contrasts with most black holes at lower redshifts. However, astronomers know that at certain gas densities, X-ray photons can become trapped, reducing the amount of X-ray emission. Therefore, this quality of LRDs could support the theory that these are heavily obscured black holes.

The team is taking multiple approaches to understand the nature of LRDs, including examining the mid-infrared properties of their sample, and looking broadly for accreting black holes to see how many fit LRD criteria. Obtaining deeper spectroscopy and select follow-up observations will also be beneficial for solving this currently “open case” about LRDs.

“There’s always two or more potential ways to explain the confounding properties of little red dots,” said Kocevski. “It’s a continuous exchange between models and observations, finding a balance between what aligns well between the two and what conflicts.”

Based on a press release by Space Telescope Science Institute.